#cypress knee museum

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Tom Gaskin Cypress Knee Museum

The Museum is an open-air arcade that surrounds the world's largest transplanted cypress tree.

Tom Sr. displayed his knees in the Florida pavilion at the 1939-40 New York World's Fair, and he still holds the only US patent (#2,069,580) on articles of manufacture made from cypress knees.

0 notes

Text

Old Florida Cracker Stuff

1 note

·

View note

Photo

如果你不學會如何去愛, 有人會教你如何去恨。 那麼你會混淆兩者。

If you don’t learn how to love, someone will teach you how to hate. Then you’ll confuse the two.

-Tom Gaskins-

Tom Gaskins (Palmdale) He was an "inland Cracker" who lived his entire life in Florida cypress swamps. His knowledge of cypress knees and swamp life was legendary. Due in large part to his influence, the cypress products industry is a phenomenon that thrives on Florida roadsides.

by Francis Baker

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tom Gaskins Cypress Knee Museum looking like its straight out of Chernobyl Diaries

#urbex#urban exploration#urban exploring#abandoned#abandoned florida#photography#bando#tom gaskins cypress knee museum

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 20 The Oodnadatta Track

Australia is a land full of wonders, with layers and layers of history - a place for discovery. Its forests and gorges are its cathedrals and its precious weathered rock art and ruins, its museums and libraries. Majestic River Red Gums mark the wide river courses which are more often than not dry beds of stones, sand and huge boulders but which, when at flood, cover huge tracts of land. Water! The essential ingredient to the stories of this mostly sunburnt land and which is central to this little story, a story about a small part of our wide brown land, the Oodnadatta Track.

Beneath this iconic outback track lies one of the world’s largest aquifers, the Great Artesian Basin which covers more than 20% of Australia. The Track crosses the traditional lands of three Aboriginal groups - in the south the Kyani people, to the west the Arabana people and to the north the Arrente people. The desert which today we know as the Simpson Desert, has three different names depending on location and is guarded and tended by these traditional groups.

A string of springs runs right through this part of the country, outlets from the deep artesian reserves. Knowledge of the location of these life-giving springs has been passed down by the traditional people of the region for 10s of 1000s of years and they have shared it with explorers and settlers alike warning them that “it isn’t the straightest route but it’s the only one if you are to survive.”

The Track is 600 odd Kms long and we have travelled it a number of times never tiring of its many faces.

The staggering enormity of Lake Eyre-Kati Thanda which lies to the north of the Track, is mind blowing and the rivers that feed the lake cover a further area of 1.2 million square Kms. Mostly it and Lake Eyre South (pictured above) are dry salt lakes but we have seen water in the southern lake from the Track a number of times. We have even walked to the edge close to the water - or more exactly as close as we could before getting totally bogged almost up to our knees – a little scary actually.

But the springs - we had stayed at and explored Coward Springs but I was keen to explore the mound springs dotted along the track and first on the list were the Wabma Karabu Mound Springs. It was like driving through a moonscape getting to these springs; this is extensive salt pan country.

It was rather unbelievable seeing raised water pools in this arid landscape; the first spring is ‘Blanch Cup’. The springs are home to amazing creatures like isopods which seem to be from another world but there are also a few varieties of land snails and fish that live in these pools. The ripples in the second pool are caused by the water bubbling up – this spring is call ‘The Bubbler’. Amazing!

Strangways Springs NW along the Track are within a heritage and conservation area. On the right is one of the last of the original telegraph poles that carried the essential line to Darwin along this line of springs; the pole is supposedly made from native cypress pine which is termite-resistant. Incidentally Anna Creek Station is the world's largest working cattle station.

This is the ‘track’ we followed as we explored Strangway Springs; the stones, we think! Here it was clear but elsewhere it was a bit of a guess. We walked about 6ks and it was pretty ‘warm’.

This is Sedge Spring, one of the mound springs at Strangways. The ledges of this small rocky spring indicate the original depth of the pool and are very fragile. The overflow from the pool creates a trickle of permanent water supporting the sedge community; the sedges are typical of many mound springs. Springs like this in this area are rather precious as many are no longer gurgling due to the number of bores that have been sunk. But they still sustain some precious life out here.

Some of the mound springs were rocky and high and Lindsay just had to climb them to see what was on top. Sadly most were extinct.

On the bottom of the pool at this spring, you could see little craters of sediment created by the bubbling spring. This spring was fringed with the small sedge, Cyperus laevigatu.

I couldn’t leave this post without sharing a few pix of plants I found – in the most unlikely and seemingly hostile environments flowers bloom. Left is a Harlequin Mistletoe, a bright flash in a parched environment. Top right is Frankenia a small grey-green mounded ground-cover with sweet little pink flowers. It is common near springs and other saline areas. I found it atop one of many extinct springs at Strangways. Lower right is samphire which grow in saline areas inhospitable to many other plants. Small birds eat their fruit.

Wandering the mound springs that day made for a pretty special birthday - starting in Coward Springs and ending at William Creek. More anon …..

#William Creek#Strangways Springs#Wabma Karabu#mound springs#Kati Thanda#Arrente Arabana Kyani#Simpson desert

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Signs and Wonders: Outsider Art Inside North Carolina"by Rodger Manley, North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh1989

Part 2

(via MONDOBLOGO: signs and wonders)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

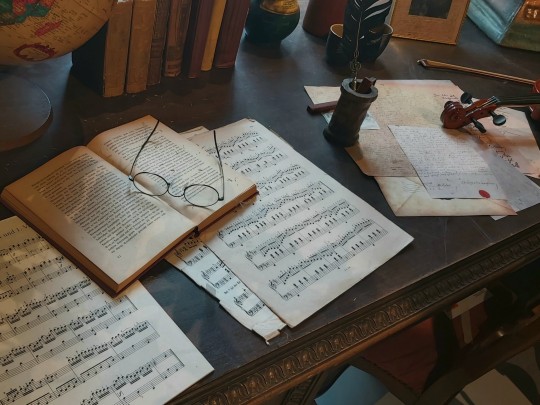

If you ever visit Budapest, it’s only a 30 minutes ride to Martonvásár with a train. They have a Beethoven museum, as he was well acquainted with the Brunswick family, and taught the young ladies to play the piano.

The museum is located in the mansion of the family, that is inside a huge English style park. With a lake. And beautiful old trees that saw Beethoven walking in their shade.

They also have interactive tours for kids about nature.

Oh, and in summer the Hungarian Philharmonics are holding a series of Beethoven concerts on the island in the middle of the lake.

Fragments of a Beethovenfest deko I found at a thrift store in Vienna - 2020

#shamelessly promoting my hometown#it is a gorgeous little town#now with reopened promenade from the train station to the mansion#did I mention the old cypress tree with cypress knees that look like little dwarves?#Martonvásár#Martonvasar#one of the Brunswick girls are rumored to be the Immortal Beloved#the older one of the sisters Teréz (Theresa) opened the first kindergarten in Hungary#the old building of the kisdedóvó houses a Kindergarten Museum that follows the different schools of teaching children throughout the ages#do I have to tell you anything else?

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

Christmas

Friday, February 4, 2022

Christmas is more than just a holiday. The trailhead for Tosohatchee Wildlife Management Area is in Christmas, FL at the end of St. Nicholas Ave.

It's 85 and sunny. Our friends in New England are enduring a dangerous ice storm. We gloat. We count our blessings that we get to be warm, even hot. Jeanne's sister told us to be prepared for temps in the 50s and 60s. "80 is really rare". But here we are. We decide to do a half day hike and start early when it is still cooler.

Tosohatchie WMA is yet another habitat -- praire with palmetto brush instead of grass. The trail is sandy and mostly dry.

There is another elegantly engineered bridge crossing Tootoohatchie Creek.

Cypress trees push up knees that are perfectly reflected in the still water.

We stop to take photos of a large vine across the trail putting out smaller liana vines down to the ground. Are they roots? We don't know.

We meet a runner who is tying strips of pink surveyor's tape to bushes along the trail. He introduces himself as Shawn "Run Bum" and immediately informs us that he holds the speed record for the Florida Trail and can do a 50 mile day. Jeanne is not impressed, having met many speed hikers on the Appalachian Trail where there are hills and mountains. 50 miles a day on a flat trail? She could have done it when she was 30.)

Shawn informs us (hastily) that he is marking the trail for a 100-mile marathon being held on the trail over the weekend, and runs off. Tim does a quick search on his phone and finds that he is controversial for claims about his speed records. He was a good topic of conversation for the next mile or so.

We are still feeling good and we are ahead of schedule when we pass the turnaround goal Jeanne had set, so we kept going. We met three people on horses and realize that there are a lot of different loop and side trails here. We turn around at the White Trail junction and retrace our steps.

The last house on St. Nicholas Ave has a large flock of chickens, geese, and cats. The fowl are running back and forth across the road while the cats recline regally on the cool pavement. The woman feeding the flock notices us waiting patiently and shoos the flock and the cats so we can pass. She is friendly and smiles when she sees us laughing.

We drive through Christmas so we can get a photo of a "Welcome to Christmas" sign, but alas. Christmas has 9 commercial buildings spread over a mile of woods. Jeanne gets a photo of the roadsign for Fort Christmas Museum Park.

We don't even discuss going, but head back to Titusville hot and tired. Jeanne takes a shower and insists on going to the beach, because her girlfriends want beach photos to envy while they scrape the ice off their cars. The other direction on Rt 50 is the Indian River with great views of Kennedy Space Center and Canaveral National Seashore. We pull into Kennedy Park, walk down to the water, pull out the scope and start identifying buildings.

Tim spots the Astra Rocket 3 that is scheduled to launch on February 5. Note: That is the launch we rushed to Florida to see that was originally scheduled for January 30. With luck, we will be able to see 3 launches, and this is clearly a great location to watch the Astra tomorrow.

A quick stop at Walmart on our way back gets us the necessities of a kitchen that we don't have at the hotel: paper towels, dish soap, sponge, and better toilet paper. We have all these items in Millie, but she is now almost an hour away. Walmart it is.

We settle to an evening of catching up on the blog and eating delicious grilled pork chops.

Note: We got behind on the blog because we were sad and didn't know how to write a humorous and entertaining blog when we were busy faking how much fun we were having. Now we are actually having fun, we know the bad news, and we aren't going to let it stop our vacation.

0 notes

Text

A Pittsburgher Undertaking Native Tree, Shrub, and Forest Restoration on a Small Budget

Our guest blogger notes that he has no formal training in gardening or botany which perhaps makes this an even more inspiring story. In the past two years this one individual (with the help of a friend) has planted 1,500 native trees and shrubs as well as numerous native forbs on about 15 acres of his own property and that of willing neighbors. His goal is to attract pollinators such as native songbirds, butterflies, moths, and other insects. His plans include planting at least 500 more native trees and shrubs each upcoming year. We invited him to share his experience, written in his own words, on this ambitious endeavor as part of a blog series inspired by our new exhibition We are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene.

Motivation

My parents taught me bird watching starting from my preteens. I finally saw my first pileated woodpecker (Brookgreen Gardens, South Carolina) at age 14. Canoeing through the Okefenokee swamp in southern Georgia/northern Florida in the spring, we would see brilliant yellow/orange-ish prothonotary warblers flitting some 20 feet away among the knees of towering cypress trees and also the flocks of honking sandhill cranes overhead. One of my daughter’s middle names is Dendroica for the warblers. The other daughter is named after the tallest tree species (if I am pressed, I am not sure if it is for giganteum or sempervirens; my father calls her “little twig”). And my son is named after the last name of the most famous modern biologist. This project for me is about giving back. I am no expert about what I am contributing here. I welcome corrections and comments. The other motivation is that this project is doable with not much money, and anyone could do this. If you do not have the land, find a willing neighbor/friend who does, and start planting natives and removing invasive plants on their property.

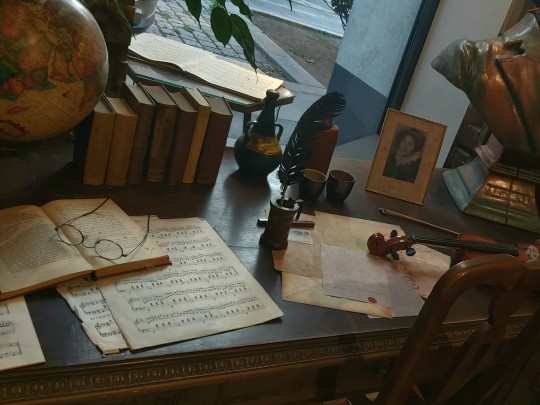

Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania are marvelous ecological areas and the birth areas of noted environmentalists such as Rachel Carson and Edward Abbey. We get plenty of rain, even in the summer, which means we do not have the droughts observed in other parts of the country. Western Pennsylvania is riddled with creeks, which are ample places to plant native trees and shrubs that will never have to be watered as the creek riparian zone will take care of them. We also have clay soil (I know I will swear about the slate rocks when digging holes with a posthole digger by hand), which holds moisture and minerals. Lots of things can grow here. Because of topography, there are many places where houses cannot be built, so there is ample space for native trees, shrubs, and wildflowers.

Pittsburgh National Park

We can think of Pittsburgh as “Pittsburgh National Park,” and the city already supports a huge biomass of bird populations such as the thousands and thousands of crows wintering here each year. If we would just plant lots and lots of flowering trees such as the dogwoods and redbuds and hawthorns and shrubs such as northern bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica), we could increase the habitat to attract more beautiful songbirds such as rose-breasted grosbeaks, cedar waxwings and scarlet tanagers to spend more of their time here. I grew up in the Piedmont area of North Carolina, and every spring we would be greeted with the explosions of the dogwoods and redbuds that are endemic in the woods. The same could be done here with our hillsides that are refractory to building houses but not to populating them with dogwoods, redbuds, serviceberries, and hawthorns.

Growing native plants in large clusters

I am no expert on native plants and have consulted with many people as well as just Googled information. Somewhere I had read of a research study in which the authors determined that the planting of 250 wild flowers of one species was necessary to get another butterfly species to appear. A guiding principle is to identify multiple high wildlife value specimens, and then plant lots and lots of each of those species. (I should note that most wildlife management principles state that diversity is better than lots of one species; in my case I am promoting clusters of diversity). If we all wanted to purchase watermelons, but the markets would only keep a few in stock, we would eventually stop making plans to go to a market with the purpose to get a watermelon. And if a bird encounters not one serviceberry tree, but instead a forest of 300 serviceberry trees, we may instead have enticed a flock of these birds. For example, I have observed a flock of cedar waxwings rushing back and forth among a cluster of black cherry trees to eat the fruit. A solitary tree would get less activity. With sufficient establishment of native trees, shrubs, and wildflowers, we may entice birds to nest in the area. The Powdermill Nature Reserve (part of Carnegie Museum of Natural History) Bird Banding project has documented the precipitous decline of songbirds, with some declines as much as 70 percent over the last 50 years. We can repopulate our yards and our woods and our cliffs along the rivers and highways with native species that will restore habitats and help stabilize the populations of the songbirds that are left and perhaps even help grow them.

Early in this project I was fortunate to get a state of Pennsylvania biologist on the phone, and he emphasized that I should concentrate on plant species that use lots of water as these species will generate lots of biomass. With the drainage creek behind by house, I am inspired to plant along its sides every step of its 1000 feet. I am on 2 acres plus. I also have multiple agreeable neighbors on similar or larger acreages, and all these neighbors have acres of woods that they leave alone and have allowed me to remove the invasive trees, shrubs, and grasses and plant the hundreds of native trees, shrubs, and forbs. I am inspired by the biologist at Indiana University who mowed an old overgrown field in Bald Eagle State Park to set back succession to an earlier stage of growth. The mowing was done in wide strips so that as those areas grew back they could mow additional areas. In the following spring he was able to observe several pairs of nesting golden winged warblers, a songbird species that has had a precipice decline in the last 50 years. While I do not expect such spectacular success, one can use the Allegheny County population data from eBird to gauge which songbird species we may be able to attract to nest in the area. In the woods behind my house, I have seen wood thrushes and hooded warblers sporadically each year. Perhaps the growing of a smorgasbord of native trees, shrubs, and forbs will entice them to lengthen their stays.

Bambi

One white tailed deer consumes 200 pounds of leaves and twig matter each month, roughly a ton per year. Typically, when one sees one Bambi, there are another 4 browsing within 50 feet, which is the equivalent of 5 tons of leaf and twig destruction each year. As a gardener, I think of Bambi as rats with long legs. While Bambi has evolved to eat everything, they have yet to develop a taste to eat galvanized steel. For this reason, metal cages are used to protect any plant at risk for Bambi. We have made metal cages from half inch mesh hardware cloth, chicken wire and 16 gauge welded wire fencing. Cages range from 1 foot high to 2 foot high, to 3 foot high to 6 foot high with diameters of 6 inches (18 inch linear fencing made into a cylinder) and 8 inches (24 inch linear fencing made into a cylinder). I am not planning to remove the cages. If I had more funds, the cages would be typically 8 feet tall and 2 to 3 feet in diameter as is done at the Pittsburgh Botanical Gardens as well as at Nine Mile Run in Frick Park.

507 trees and shrubs planted in November 2017

In November 2017, we planted

100 northern bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica) seedlings, one to two feet in lengths (www.coldstreamfarm.net)

100 Norway spruce (although it is not a native, Norway spruce is recommended by the Penn State Extension, and I hope to someday attract crossbills which also fly over to Norway) four-year transplants, 12-15 inches in height with 12-15 inch long roots (Mussers Nursery, Indiana County, PA)

100 red-twig dogwood (Cornus sericea; www.coldstreamfarm.net) two to three foot in length seedlings

102 two to three foot long pagoda dogwood stakes (Cornus alternifolia; www.wholesalenurseryco.com/product/pagoda-dogwood-stakes/)

100 eastern white pine four-year transplants, 12-15 inches in height with 12-15 inch long roots from Mussers

5 black willows from Mussers

Soon after planting, 4 inch by 6 inch rectangles of paper were folded over and then stapled in place over the terminal buds of the white pines to protect them from winter browsing by the deer

In spring 2017, I got 300 six-year eastern white pine transplants (Mussers Nursery) that had roots of 2 feet in length. It took me multiple weekends and after work hours that spring to manually posthole the holes for these six-year transplants. Rotting in the basement while waiting to be planted, at least 100 trees did not survive the planting process/the summer.

I learned my lesson. I purchased a gas-powered auger with a 6-inch diameter by 30 inch long bit from Home Depot online. The 6-inch bit is much easier to dig with than the 8-inch bit. My volunteer and I and the gas-powered auger were able to dig over 100 30-inch deep, 6-inch diameter holes in just a couple of hours. This time we got four-year white pine transplants with only 15-inch length roots and planted them the same day we picked them up. The eastern white pines will grow to 100 feet and the spruce trees should grow to 50 to 75 feet. It is like planting an ‘instant forest’. Half inch mesh two-foot hardware cloth cut into two foot sections to prepare cylindrical cages were used to protect the red-twig dogwood seedlings. Each cage was buried about 4 to 6 inches to prevent deer and weather from knocking over the cage. I purchased 4 rolls of 100 feet by 6 feet of 14 gauge welded wire fence (Deacero Steel Field Fence 6 ft. H x 100 ft. L (7745)) from Ace Hardware, and what with shipping cost a total of about $500. We made 50 cages from each roll using tin-snips. 102 cages were used for the planting of the pagoda dogwood cuttings. About 12 inches of these 6 foot cages were submerged into the hole to prevent deer and weather from knocking them over. Native dogwoods other than the common flowering dogwood (Cornus florida) were chosen because of the flowering dogwood’s predilection for Anthracnose, a fungal infection that can make the tree look ugly and potentially die. The pagoda dogwoods were planted in moist soils, and the tall cages should protect them from the deer and allow the dogwood to eventually achieve 20 foot heights.

The costs for planting in November 2017 The 100 spruce, 100 white pine and 5 black willows from Mussers cost $341 plus the cost of gas driving to pick them up. The 100 red-twig dogwood ($146 plus shipping) and the northern bayberry ($172 shipping included) were from Cold Stream Farm. The 102 pagoda dogwood stakes shipped from a Tennessee wholesale nursery were $187. The 200 foot of 2 foot hardware cloth to make the 100 cages for the red-twig dogwoods was about $140. And the pagoda dogwood cages cost about $250.

So the cost of planting 507 trees and shrubs was about $1250 or about $2.50 total per plant which overall is economical. Labor is considered to be voluntary and is not included in these calculations. On the other hand, I am still living in my old unfixed house with my ancient toilets of which one takes 20 seconds to flush and is relegated only to flushing liquids. In 2015 when I got the house, I had repair insurance for the first year though I was unable to convince a plumber that a toilet that took 20 seconds to flush needed to be replaced under that home repair insurance plan. My skimping on fixing my old house allows me the funds to plant a forest that will live for ages.

Invasive plant garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) removal With garlic mustard, I like to pull the first years of this biennial plant whereas others suggest pulling the second year flowers and leaving them to dry and die and decompose. Rosettes are hand pulled and can be left to dry out and die. First year plants including the entire root can be pulled after rains that softened up the grounds. The removed plants are placed in the crooks of tree branches to allow the garlic mustard to dry out and die and decompose.

Example future project: American woodcock project One section of the woods is fairly open with a couple of acres of privet with moist soil and the idea is to replace the privet with alder (300 alder seedlings can be purchased from Mussers Nursery for $150 total) to improve the area to possibly attract woodcock so that the birds have space for their mating dances and space to look for earthworms. We have a heavy duty hand weedy-shrub pulling device (Pullerbear) which can be used to pull invasive shrubs such as privet, multiflora rose, and Japanese barberry out of the ground.

Some sources of information on the web

Landscaping for Birds - A go to website from Cornell Ornithology. I use this website to help decide which classes of trees and shrubs to plant in mass.

Beechwood Farms - Audubon Society of Western Pennsylvania. Beechwood Farms has an excellent native plant nursery.

eBird - (dates and populations and locations) of birds in Allegheny County from ebird.

PSU Extension Lawn Alternatives - One of many excellent sites from Penn State Extension.

Garden Planner Dripworks - Where I get my drip irrigation supplies.

Prairie Moon - This is where I purchase about a hundred-dollars of native forbs and shrub seeds each January.

Howard Nursery - Inexpensive trees and shrubs that can be ordered each January through early March from Howard Nursery. Presently have been getting grey dogwood and smooth alder seedlings from them. Recommended to order in January as soon as the website opens as they run out.

Musser Forests - Mussers Tree Nursery. Being only about a 75-minute drive from Pittsburgh.

Cold Stream - Cold Stream Farm wholesale nursery. Relatively inexpensive source for northern bayberry, dogwood shrubs, buttonbush seedlings and more.

Audubon Native Plants - Audubon native plants database. For each plant, there is a listing of which native birds are attracted.

Wildflower - Wildflower database

This blog series depicts Pittsburghers and their commitment to improving the local environment to celebrate our new exhibition, We are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene. Each blog features a new individual and explains the ways in which they are helping in areas of sustainability, conservation, restoration, and climate change. This blog was written in the author’s own words. Any opinions in this blog are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent that of the museum.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mavromati to Bassae to Mount Taygetos

My holiday journal from 2007 (originally posted to MySpace on June 11th, 2007)

May 11th, 2007: Mavromati – Bassae - Mt. Taygetos

When you drive, you see a lot of the back of your hands. I can see how swollen the sprained right thumb is. I can see neither the two tendons that run to it, not the one for my forefinger – it's all a taut, shapeless bulge.

As I drove I became aware of an ache in my upper back; below, but close to, my left shoulder blade. I decide I'll have to have a look when I get to my next stop and have access to a mirror.

I awoke early – 7 am or so. Sleep had been a bit fitful – turning over is no longer spontaneous but, instead, calls for a lot of preparatory shuffling and weight shifting, using bits of my anatomy that aren't scuffed or sprained or tender.

I read in bed until 8am or so, then got up and went to the shop to buy some yoghurt and juice for breakfast: I will eat the banana with the yoghurt and save the apple for lunch. (It is a big apple). Once I'd done my ablutions and a bit of first aid, I went to settle up and go to the museum and site.

The museum did not exist six years ago – but is small, elegant and well labelled. I was most impressed. It is clear from this, and the continuing work at the site, that funds are available and Messini is being developed for visitors. I am ambivalent about that – it is clearly much more accessible to visitors, of whom there will be more, and the buildings and artefacts themselves will be conserved and restored to a limited extent. What is lost is the sense of discovery and freedom that was so evident when I was last here with Jason. I had a nude picture taken on the archon's seat in the stadium – no chance of that now!

The site is well conserved, and work continues to uncover more. There were lots of groundskeepers and builders and the like, and an exuberant group of teenagers from Kalamata Grammar School, who were keen to say hello, discover where I was from and practice their English and be in photos.

Wild flowers abounded as usual and there were lizards who were less fleet of foot than their colleagues in Delphi – or was it the early hour? Doubtful – it was well in the 30s C by 10am.

There were startlingly fierce wasps of alarming size – red with two yellow bands to warn. The usual blue bees drifted clumsily about and lots of butterflies – mauves, blues, reds, whites and yellows dancing past.

I looked at Arsinoe's fountain (mum to Asklepios, who sanctuary was the focal point of worship in Messini). It is fed from the Klepsydra spring, which runs yet in the modern village and from which you can fill your water bottles. The water then courses through the ancient city, visible here and there, before making a cooling appearance in the gymnasium complex. The city centre is a planned build, as indeed is the whole city.

For centuries the Messenians were Spartan helots (slaves), brutally subjugated. They rose in revolt but were crushed. With the decline in Spartan power after the Peloponnesian War (they beat the Athenians after a 40 year slog but exhausted themselves in the process), the Thebans under Epaminondas (3rd C BCE) stepped into the breach – defeating the Spartans at Leuctra and ensuring the newly liberated Messenians would maintain their independence in a purpose built, democratically planned, fortress city. The walls at Messini are 9km in circuit and lots of sections still stand proud. The most impressive sections are at the Lakonian Gate, which you still drive through to reach Mavromati.

Around the agora, the Temple of Asklepios, the Sanctuary of Artemis, the council chamber and agora are compact and delightful in design and execution. Little gems.

The city itself is built on gently sloping ground: as it falls away, a gymnasium complex and stadium carry the eye into the valley stretched out below: vineyards, olive groves – as there have always been. The stadium is much restored – the seating is cleared, levelled and sections beyond the retaining wall, landscaped.

The Heroon, inaccessible 6 years ago, is pristine and impressive, as it was intended to be. A real statement of local power and political supremacy by the prominent local family who had supplied Rome with a Consul in the 2nd C

The section of wall and the tower nearby have great resonance for me. If I call the tower the BJ tower you will grasp why. Had I two reliable thumbs, I might have climbed up again and seen what the view was like 6 years on. The memory of that afternoon caused a stir in the loins. Interesting. Not that the Jason is an unlikely object of sexual desire – he was then, and is still (I am sure) a definite hottie. At least, so I found him. But the most profound connection was not sexual and the fracture caused by the manner of the break up was so traumatic that I doubted my capacity to manage it. It has taken years for me to begin to get a grip on that relationship and make some (fragmentary) sense of it. What surprised me was not the sexual passion that stirred but that, given the gall and wormwood associated with J, that the fire was not immediately extinguished.

Scampering about, I took a few photographs and then set off on the long mountain drive to Bassae, and the Temple of Epicurean Apollo there. Designed by Ictinus (Parthenon fame), it is presently undergoing long term conservation work and is protected by a big tent. I am not sure what I will see – there was little 6 years ago, but the drive is superb.

From my digs, I had a panoramic of Mavromati... the village lay to the left, the ancient site below, among cypresses, an in the far distance - the plain leading to Kalmata. So, I swung out on the day’s drive.

There were no tunes on this drive – just birdsong, the slick of the tyres, the changing note of the engine and the dolorous tink-tonk of goats' bells. The scenery was wild and rugged – with gorse enlivening the hillsides and verges all around. The Fingers of God pointed to a blue sky. The slopes were bursting with yellow gorse as I climbed towards Bassae,

As I rounded one bend, some 10km from the temple, I heard a snatch of conversation J and I had had that summer in 2001. There are evident signs of terraces as you slow to navigate the hairpin – and we spoke of those ancient farmers and the work involved in levelling, wall-building, and conserving the e precious soil – safeguarding your olive trees in an unforgiving landscape.

There were glorious flowers at Bassae - a meadow carpet and hardy alpines clinging to crevices. And beehives.

From the Temple it was another run to the south – on a different road this time, to take me to the busier thoroughfares that lead to Kalamata

The town will be familiar to any Greek olive enthusiasts. It was a lush drive, and it took me past Figaleia – another J stop off from the past. This time there was an old German at the spring – asking me directions to Platania.

There was no sign of the ancient and massive land crab who inhabited the old spring house, nor the little scamperers who were the up and coming residents. I gave the German – who could be me in 20 years (travelling alone, doughty, and well set up for a picnic) – some directions in my best German and set off again.

From Figaleia, a slow descent before crossing the Taygetos range.

I want to take the road over Mt Taygetos – the great chain that separates Messenia from Lacedaemon (ancient Sparta). I intend to stop in a guest house at the top of the Langhada Pass – and have an easy run into Sparta tomorrow. The drive was another stunner. It is easy to see why ancient Sparta was never fortified – unlike most Greek cities. The mountains, and the Spartan army - was defence enough.

I approached Mt Taygetos from the west and then climbed the ridge - on a spectacular road, arriving at the guest house – a little like an Alpine chalet, really, at a little after 6pm. So I can have a leisurely evening. A brew, a quiet read for a while, then a shower and first aid session. I checked my back – the source of the pain is evident – three serried red weals that relate to vertebrae that were skittered on as I made that clumsy forward roll. Both they, the knee, and the arm are beginning to show big, nasty looking bruises, as well as the black-scabbed craters that mark skin loss. The right hand's wounds look clean but the skin loss is so great they will be days acquiring a protective scab. More dressings for now…

[ NOTE: I had fallen whilst racing in the stadium at Delphi the day before - against non-one - just running full pelt for the finish line. I fell on a patch of uneven ground - a depression meant I was thrown off-balance and my trailing foot could not catch up: I nose dived into the gravel and earth at 20+ mph. To save my face I extended my right hand and then rolled onto my left shoulder. This was the cause of the injuries. I learned subsequently that I’d broken two bones in my right hand as I used it to protect my face].

OK. Enough of the health update: time for ouzo, a photo edit, then off to find some food. It's just turned 8.30pm here.

Today was brought to you by the colours yellow,

more yellow

and Cypress green,

and by the fragrances of gorse,

thyme

and oregano.

Well, now, high up in the pass, it's all pine resin!

Ciao for now,

d xx

PS – back from eating.

Staying at the top of the mountain, I had to drive 12km down it to find a place to eat – a recommended taverna in Tripi. It was very busy – with people arriving until well after 11pm – I left at 11.30pm. The customers ranged from little kids to grandparents – often in family groups – with the kids circulating and burrowing out anything that interested them. Me, of course – alone, with a book and his food. It was a good spot – food was as good as suggested and the atmosphere warm and friendly. The two waiters were identical twins – mid 20s at a guess, and absolutely indistinguishable. Much more so than the 'identical' twins in our family – who already look very different as teenagers. The owner of the taverna took a great delight in me and my limited but brave Greek. When it was time to pay, he would not let me include the coffee I had taken to conclude the meal – and insisted on giving me a dessert, to boot, before I left. But this I find with the Greeks, as a people: they consistently welcome and celebrate visitors – when they make a demonstrable effort to pay a modicum of respect the country they visit by learning at least something of the language.

The drive backup the mountain hairpins was a 20 minute thrill. Once home, I went out on to the balcony to look at the night sky. It presented a panoramic view of unearthly beauty. Diamonds on black velvet.

I had not seen such a sky since I was last on Rum, one of the islands off the west of Scotland. The reason was the same: no light pollution.

We have raised a generation of children who never see the night sky, still less are entranced by its constellations and the myths they speak of. There are some 6000 stars in the night sky – few of us town and city dwellers ever see more than a few hundred.

And so to bed – midnight…

The link takes you to some of the photos from that illustrate the blog: https://www.flickr.com/gp/damiavos/wy7eSH

#greece#holiday journal#mavromati#bassae#mount taygetos#peloponnese#damian's writing#road trip#messene#figaleia

0 notes

Photo

Tom Gaskins Cypress Knee Museum which opened in 1951 near Palmdale. Set up as an open-air arcade, the museum contained glass display cases which were filled with hundreds of knees. Most were named for the shape they resembled, or at least what Tom thought they looked like. Behind the gift shop stretched a 3/4 mile cypress knee catwalk. Hand-built by Tom himself, the catwalk was nothing more than a series of 2x4s cobbled together and held up high in the air by cypress poles sunk into the swamp. It ran past Tom’s experiments in “controlled knee growth,” which began in 1938. Tom attempted to alter the shape of selected knees by carving designs into them, shoving bottles into them, and flattening them with heavy weights. Full history and photo gallery here: http://ift.tt/2srJOLT http://ift.tt/2rHUGIv

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Retracing Truman Capote’s Moment in the Mediterranean Sun

Long before the alcohol and depression, the drug-fueled nights at New York’s Studio 54 and the promise of a Proustian novel that would never fully materialize, Truman Capote was heralded as one of the country’s most promising young writers. It was this Capote who met fellow writer Jack Dunphy in 1948. The two would end up devoted companions for 35 years. But first, Capote needed to win him over. So he hatched a plan: they would head to Italy.

After brief stopovers in Venice, Florence, Rome and Naples, the couple headed to Ischia, a volcanic island off the coast of Naples. They trekked by horse-drawn buggy, with children clinging to their carriage, and bleating goats scurrying past, to Forio, then a small fishing village, where they stayed for nearly three months.

That time would reverberate: It cemented the still fragile legs of the new relationship, and it established for Capote a routine that would serve him well — escaping to the Mediterranean to write.

“Jack was very much part of the equation. He wanted to travel, and Truman wanted to please him,” said Gerald Clarke, author of the authoritative “Capote: A Biography.”

“But Truman was also pleasing himself. Though he came from a small town in Alabama, he loved New York, loved it so much that he found it hard to write when it was so tempting to go out on the town,” Mr. Clarke told me. “New York was a kind of addiction. He realized that if he wanted to write — and that’s all he wanted to do — he would have to do it elsewhere.”

While Capote would rise to become arguably New York’s greatest literary and social lion of the ’60s, whose iconic Black and White Ball at the Plaza hotel in Manhattan in 1966 would be called the “party of the century,” with boldfaced names from Frank Sinatra to the Maharani of Jaipur mingling behind costume masks, the Capote who bunked in Forio knew his best work could only be done in self-imposed exile.

His time living in the small coastal towns and villages of southern Italy and Spain allowed him to produce a remarkable output that matched his outsized ambition. Last spring and summer, I went in search of these seaside idylls, hoping to retrace a long ago golden boy’s moment in the sun.

On a cool, crisp morning last May, I boarded a ferry from Naples, watching the city’s pastel-colored buildings give way to the blur of glamorous Capri in the distance. An hour and a half later, I pulled into Forio, on Ischia’s western coast, and spotted the Pensione Di Lustro, the couple’s former residence, just opposite the small, palm-tree lined harbor.

“It is the pleasantest pensione in Forio, an interesting bargain, too,” wrote Capote in his 1949 essay “Ischia.” For about $200 a month, they had “two huge rooms with great expanses of tiled floor” overlooking the sea, along with two five-course meals a day.

Ischia’s fortunes have risen markedly over the years, with a thriving tourism scene built on its natural thermal springs. Yet little has changed at the Pensione Di Lustro, where Capote and Dunphy were only the ninth and 10th American guests since the pensione was established, and where the playwright Tennessee Williams also joined them briefly.

No. 3, Capote’s, still looked much as he had described it, a large room with a high, vaulted ceiling, where I could imagine him toiling away on “Summer Crossing,” a previously tossed aside novel that he had once again picked up and was published posthumously in 2005.

In the small blue-and-white tiled kitchen of the 10-room pensione, I found Gioconda Di Lustro, who at 19 at the time of the couple’s stay was their cook and maid, and figured prominently in Capote’s “Ischia” essay. “Gioconda speaks no English, and my Italian is — well, never mind. Nevertheless, we are confidantes,” Capote wrote.

“He was very spirited and always animated,” Ms. Di Lustro told me in Italian, recalling how they would bake together in that very kitchen.

Gray-haired yet still quite sturdy at 88, Ms. Di Lustro now owns the hotel with two daughters, Maria Teresa and Giuseppina Di Lustro. The five-course lunches have been done away with, but that evening, I sat down to a lengthy meal similar to what Capote and Dunphy would have enjoyed — starting with a delicious tomato-and-eggplant risotto and ending with a traditional pastiera cake — all cooked and served by Ms. Di Lustro and her middle-aged daughters. (The cost? Still, as Capote had remarked, “an interesting bargain” at 70 euros, or $79, for dinner and a room that night.)

But Capote did more than just work and eat well in Ischia. He was also mesmerized by the island’s primitive beauty, whose appeal, he wrote in his essay, was in its “straight-dropping volcanic cliffs,” with rocks below like “sleeping dinosaurs.”

Armed with a map dotted with markings made by Ms. Di Lustro and her two daughters of where they thought Capote and Dunphy might have gone, I headed off to see how much of it remained.

On a sloping path toward the sea, where spotted green lizards darted by my feet, I found that I had Cava dell’Isola, a small beach that’s often crowded in summer, all to myself.

But my favorite spot was further south, past small citrus groves heaving with lemons, near the pretty, car-free village of Sant’Angelo. While a number of sprawling thermal parks have sprung up along the island, the hot springs of Sorgeto, frequented since Roman times for its naturally heated waters, remains its most dramatic.

Situated at the bottom of a vertigo-inducing set of steps, its splendor comes all in a rush, with the crashing of the waves amplified by immense cliffs that enclose the bay on three sides. My timing turned out to be off, though — the high tide rendered the waters stone-cold — but wading knee deep into a nearby grotto, I found small pools of steaming hot water, an inkling of Sorgeto’s famed lures.

Capote’s time in Ischia established a productive routine, one that his Random House editor, Robert Linscott, recognized. A year later, Capote and Dunphy headed back to Italy in April, this time to Taormina on Sicily’s eastern coast. But when the editor got wind that Capote wanted to leave the island, Linscott practically forbade him from doing so without a completed book manuscript.

That manuscript about an unlikely group of outcasts hiding out in a treehouse in the Deep South, which Capote wrote in its entirety in the hilltop town of Taormina, would be published as “The Grass Harp” in 1951. Looking closely, glimpses of Capote’s Taormina come through in the book.

These days, the Italian resort town draws both the international jet set and flag-carrying tour guides. But the seaside town to which Capote and Dunphy arrived was far quieter, still recovering from the aftermath of World War II.

On a visit last June, I found Taormina’s small center teeming with crowds, but their numbers dissipated as soon as I walked out of the Porta Messina, the town’s historic northern gateway. Past two more stone arches, I found Villa Britannia, whose young owner, Louisa Vittorio, has a unique claim to Capote’s literary heritage here: Various family members including her father, Nino Vittorio, are among the colorful characters in Capote’s 1951 essay “Fontana Vecchia,” and still live on the same narrow street.

That essay takes its name from Capote and Dunphy’s residence in Taormina, a rose-colored house situated diagonally above Villa Britannia. While Fontana Vecchia is a private residence, long owned by Ms. Vittorio’s cousin, Salvatore Galeano, and not normally open to the public, they gave me a special tour.

And when I stepped out onto its terrace, clung precipitously off the hillside, it struck me: While Capote, as a young boy in Alabama, often escaped with his childhood friend, the writer Harper Lee, to a backyard treehouse — the obvious model for the treehouse in “The Grass Harp” — here, too, perhaps, was another inspiration, a soaring sanctuary far removed from the social demands of his Manhattan life.

At Villa Britannia, I tried to slip into Capote’s writing-and-sea routine, working in the morning on the private terrace of my “Truman Capote” suite, surrounded by cypress trees and their cones, with a view of the Calabrian shores in the distance.

It was hard to peel myself from the exquisite villa and its tiny garden of jacaranda and oleander blooms to go to the sea. But I was rewarded for making the trek downhill — made infinitely easier by cable car, installed in 1992 — with the stunning Isola Bella, Capote’s favorite beach, a curving slip of pebbly shoreline that overlooks a beautiful nature preserve of the same name.

Seven years later and back in New York, Capote stumbled across a headline in this paper — “Wealthy Farmer, 3 of Family Slain” — in November 1959. With the help of his childhood friend, Lee, Capote spent roughly three months in the high plains of western Kansas to research what was originally conceived as a relatively short article for The New Yorker. When that limited scope soon gave way to what would run as four installments in the magazine and become “In Cold Blood,” his “nonfiction novel” much praised for its atmospheric, filmic detail, Capote once again headed across the Atlantic.

With Dunphy by his side and suitcases of typed notes, Capote in April 1960 arrived in Palamós, a vibrant seaside town north of Barcelona long considered a retreat for city dwellers.

On a searingly hot sunny morning in early August, I met Maria Àngels Solé, a tour guide at the Fishing Museum, which offers a “Palamós of Truman Capote” tour most summers.

We walked up the pedestrian-only Carrer Major, the town’s bustling main street, where she pointed out the locations of the shops Capote frequented. Near the port, we found the plaque that marked the location of Capote’s first villa, a five-story apartment complex in its place.

Two of Capote’s other homes are similarly long gone, said Josep Colomer, the longstanding owner of one of Palamós’s most storied and oldest hotels, Hotel Trias. I had arranged to meet him and his wife, Anna Maria Kammüller, in the lobby, where they said Capote often came in the mornings to read his newspapers over a gin martini.

While the town of Palamós is much changed, Castell-Cap Roig, a protected area spread over 2,700 acres of red granite cliffs, towering pine trees and secluded coves, remains much the same. Among its smattering of houses is a large villa, above the cove of Sanià, which Mr. Colomer said he had arranged for Capote to rent during his last spring and summer in Palamós.

The next day, that’s where I headed, hearing only my own footfall on dried pine needles, and the incessant siren song of humming cicadas along a forest path.

Then after about a 20-minute trek, with pine trees giving way to a field of wispy yellow and pink wildflowers, I saw it, Capote’s last — and grandest — home on the Mediterranean, a whitewashed villa with a dark green gate. Here he had toiled on the third, and longest, portion of “In Cold Blood,” and entertained the occasional famous friend, including Gloria Vanderbilt, whose yacht was anchored in the cove.

The novel would be far lengthier and more complex than anything Capote had ever attempted before. Researching such a gruesome subject, getting so emotionally close to the murderers — and watching their executions — would take a psychological toll.

Sanià cove isn’t accessible to the public by foot, so I headed down a steep, stone path to Canyers, a cove adjacent to Capote’s private sanctuary. There, I found water so crystal clear I could see straight through to the seashells on the rocks as I waded in. Gazing out at the endless blue-green of the sea, I felt an utter stillness and calm that I imagined Capote, too, must have felt looking out onto the water.

Capote considered purchasing either the Spanish villa or another house nearby but acquiesced to Dunphy, who loved to ski and was eager to return to Verbier, Switzerland where they had previously spent several winters. After they left the Spanish coast in the fall of 1962, they never lived together along the Mediterranean again. In 1966, “In Cold Blood” became a best-selling book, marking both the height of Capote’s fame and achievement, but also the beginning of his eventual downfall.

Before all that, though, he had his craggy cliffs, his secluded beaches, the exquisite sensation of cool seawater on sun-warmed skin — but above all, his great love — the charmed contours of the private life of a public writer still in his prime.

Ratha Tep, based in Dublin, is a frequent contributor to the Travel section.

Follow NY Times Travel on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.

Sahred From Source link Fashion and Style

from WordPress http://bit.ly/2Wp7leu via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

Tom Gaskins’ Cypress Knee Museum

#urbex#urban exploration#urban exploring#abandoned#abandoned florida#old florida#tom gaskins cypress knee museum#abandoned building

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

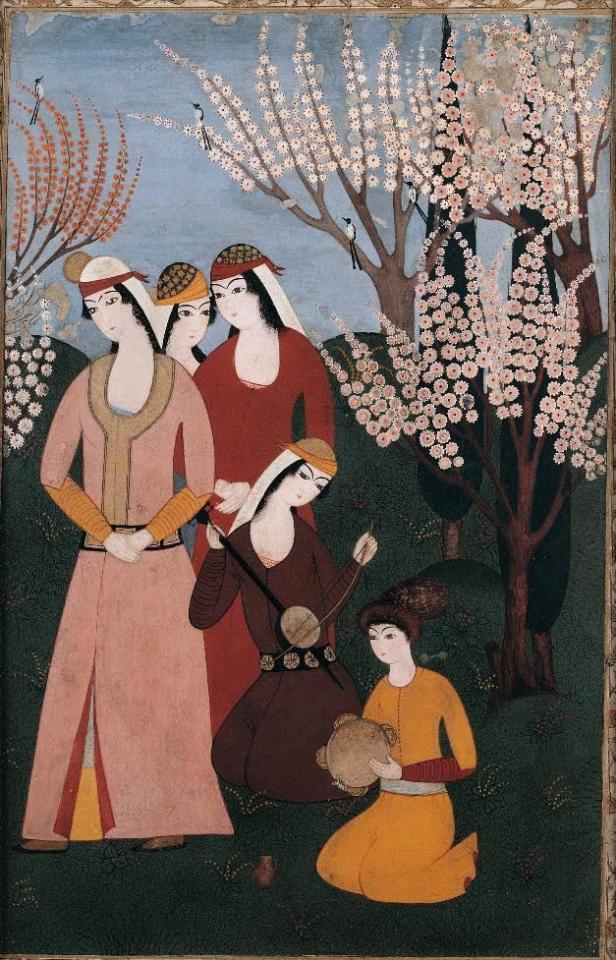

MWW Artwork of the Day (10/21/17) Ottoman miniaturist (fl. early 18th c.) A Musical Gathering (c. 1703-30) Ink, opaque watercolor & gold on paper, 38.2 x 24.8 cm. The Aga Khan Museum, Toronto

This colorful ensemble of musicians and entertainers illustrates the royal taste for music and dance in the Ottoman world, an interest shared with other Islamic and European courts. While single-page paintings had been introduced to the artist’s repertoire over a century before, the formation of the figures and the fact that they appear to direct their performance to an audience at their right suggests that this image formed one half of a double-page manuscript painting. Falling in line with earlier princely images depicted in Persian illustrated manuscripts, the audience would probably have consisted of a king and his attendants or courtly lovers enjoying a musical interlude in the country. Three women stand next to the musicians, dressed in peach- and crimson-coloured robes, while a fourth sits on her knees to play the ektar, a one-stringed lute. Meanwhile, a young boy sits to the left of the lute player and taps his tambourine to the music. The painting, once mounted on an album, retains part of a margin that was decorated in gold vegetal scrolls. While illustrated Ottoman manuscripts first tended to emphasize history and geography -- sieges and battles and maps of conquered territories -- this painting seems to fit into a later interest in the more peaceful aspects of courtly life. It probably dates to the early eighteenth century, during the reign of Sultan Ahmad III (r. 1703-30 CE), when war was not at the forefront of the political agenda and the sultan could refine his artistic taste, inspired by seventeenth-century Persian painting. Yet Ottoman features also abound: the cypress trees and cherry blossoms surrounding the musicians are reminiscent of such depictions on Iznik tiles made for the Ottoman court in the mid-sixteenth century under Süleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520-66 CE).

(from the Museum website)

0 notes

Text

Things to Do in Vancouver this Weekend: April 13, 2017

It’s a weekend of vibrant colour! You know it’s spring when the fields of Abbotsford turn to multi-coloured bands of thousands of tulips. There are also the vibrant Vaisakhi day festivals this weekend, which mark the Sikh New Year and, for Easter, the pastels of bunnies and chocolate egg hunts are all over the city.

Friday | Saturday | Sunday | Ongoing

Friday April 14

Abbotsford Bloom Tulip Festival Where: 36737 North Parallel Road, Abbotsford BC What: A chance to marvel at 10-acres of rainbow-coloured fields featuring more than 2.5 million tulips in a vivid display of breathtaking beauty. Visitors are invited to enjoy the view, get up close with the blooms, tiptoe through the expansive tulip fields, pick their own spring bouquets in the sprawling u-pick tulip field or purchase pre-picked tulips in the “Bloom-Mobile”, an on-site flower shop. Runs until: Sunday May 7, 2017

Bill Reid Creative Journeys | Image via the Canadian Museum of History

Bill Reid Creative Journeys Where: The Bill Reid Gallery What: Celebrating the many creative journeys of acclaimed master goldsmith and sculptor Bill Reid (1920–1998), this exhibition provides a comprehensive introduction to his life and work. Runs until: Sunday December 10, 2017

Tinder Tales Where: The Fox Cabaret What: Professional/amateur daters, storytellers, comedians, and everyday people confess their most outrageous Tinder Tales and other online dating disasters live on stage.

How to Be

How to Be Where: The Cultch What: A close up look at how we think we “should” be, how we feel others “should” be, and the beautiful failure of it all. Runs until: Saturday April 15, 2017

Vancouver Whitecaps vs. Seattle Sounders

Vancouver Whitecaps vs. Seattle Sounders Where: BC Place Stadium What: It’s soccer! Classic Vancouver vs. Seattle, come see which rainy city will triumph.

Snoop Dog

Snoop Dog Where: Rogers Arena What: It’s Snoop Dog’s Wellness Retreat Tour with guests Cypress Hill, Method Man & Redman and Berner.

Prozzäk Where: The Commodore Ballroom What: The 90’s duo, Simon & Milo, known for their ear worm hits Sucks To Be You and Strange Disease, spent much of 2016 cryogenically frozen, in preparation for one of their biggest years since the 90’s.

Redpatch Where: Studio 16 What: Opening on the 100-year anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge, this moving production follows the story of a young Métis, volunteer solider from the Nuu-chah-nulth nation of Vancouver Island deployed to fight in the First World War. Runs until: Sunday April 16, 2017

Generation Post Script

Generation Post Script Where: Studio 1398 What: It is two generations into the future. What is left of humanity survives in space stations in orbit around our planet. Interstellar travel is not yet possible and Earth is uninhabitable. A misfit group of college students of the “post script” generation—the first to be born in space—bond over their shared anxieties and a desire to reconcile what happened to the rest of their species. Runs until: Sunday April 16, 2017

Room 2048 Where: Firehall Arts Centre What: Multimedia dance theatre exploring the socio-political realities of the Cantonese diaspora told through digital light design, bombastic pop music, fog, and the Chinese body.

Saturday April 15

top of page

The 9th Annual Great A-mazing Egg Hunt (day 1 of 2) Where: VanDusen Gardens What: The Easter Bunny is busy mapping out a hunt in the garden and through the maze, and preparing the chocolate treats to reward the hard-working egg hunter. Hang out and enjoy some fun crafts & activities and explore the 55-acre garden.

Vaisakhi Day Parade Where: Vancouver/Surrey What: Every April, millions of Sikhs world-wide celebrate Vaisakhi Day, a day that marks the New Year. Considered one of the most important festivals in the Sikh calendar, parades celebrating the event are held in Sikh communities around the world.

The Damned

The Damned Where: Commodore Ballroom What: Cited as one of the most influential punk groups of all time, The Damned contributed vastly to the gothic rock genre and influenced an entire generation of future hardcore punk bands such as Black Flag and Bad Brains, with their fast paced energetic playing style and attitude.

Almost, Maine Where: The Cultch What: One cold, clear Friday night in the middle of winter, while the northern lights hover in the sky above, Almost’s residents find themselves falling in and out of love in the strangest ways. Knees are bruised. Hearts are broken. Love is lost, found, and confounded. And life for the people of Almost, Maine will never be the same. Runs until: Saturday April 22, 2017

Nochella Where: The Biltmore What: Playing 2017 Cochella acts all night long and yes – you are encouraged to dress in your festival wear.

Sunday April 16

top of page

The 9th Annual Great A-mazing Egg Hunt (day 2 of 2) Where: VanDusen Gardens What: The Easter Bunny is busy mapping out a hunt in the garden and through the maze, and preparing the chocolate treats to reward the hard-working egg hunter. Hang out and enjoy some fun crafts & activities and explore the 55-acre garden.

The Tree of Wooden Clogs

The Tree of Wooden Clogs Where: The Cinematheque What: Winner of the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1978, Ermanno Olmi’s elegiac portrait of peasant life in late-19th-century Lombardy is rendered with a sublime understatement, humanism, and lyricism that recaptures the best of Italian neorealism. Made with an ensemble cast of non-professionals, and with an exquisite appreciation for the everyday.

Monty Python’s Life of Brian Where: The Rio Theatre What: Set in 33 A.D. Judea where the exasperated Romans try to impose order, it is a time of chaos and change with no shortage of messiahs and followers willing to believe them. At it’s center is Brian Cohen, born in Bethlehem in a stable (next door to Jesus’ manger) who, by a series of absurd circumstances, is caught up in the new religion and reluctantly mistaken for the promised messiah.

Res-erection 2017: A Zombie Jesus Burlesque Show Where: The Biltmore What: All your zombie fantasies come to life, burlesque-style. Plus a zombie dance moves contest and a post-zombie-apocalypse dance party.

Ongoing

top of page

The Watershed

The Watershed Where: Gateway Theatre What: Celebrated documentary theatre artist Annabel Soutar leads her family on a cross-Canada journey, probing the future of our dwindling natural resources. By innovatively dramatizing insightful sets of interviews with scientists, government officials, activists and business leaders, The Watershed uncovers the complexities underlying the environmental, economic and political stakes of oil production and fresh water preservation in Canada. Runs until: Saturday April 15, 2017

World Ski and Snowboard Festival Where: Whistler, BC What: A 10 day and night showcase of some of the best of mountain culture, music, arts and snow sports. Runs until: Sunday April 16, 2017

Generation Post Script

Generation Post Script Where: Studio 1398 What: It is two generations into the future. What is left of humanity survives in space stations in orbit around our planet. Interstellar travel is not yet possible and Earth is uninhabitable. A misfit group of college students of the “post script” generation—the first to be born in space—bond over their shared anxieties and a desire to reconcile what happened to the rest of their species. Runs until: Sunday April 16, 2017

Vancouver Special Where: Vancouver Art Gallery What: The first iteration of this series and it features works by 40 artists produced within the last five years—Vancouver’s post-Olympic period. The exhibition includes many emerging artists as well as those who are more established but whose ideas were prescient. Some are recent arrivals to Vancouver, while others are long-term residents who have already made significant contributions. Others are nomadic, less settled in one place and are working energetically between several locations. Runs until: Monday April 17, 2016

Nat Bailey Stadium Winter Farmers Market

Nat Bailey Stadium Winter Farmers Market Where: Nat Bailey Stadium What: Don’t fret the summers Farmers markets packing up – winter is here, and you can still shop local for fresh produce, preserves, baked goods, and crafts. Runs until: Saturday April 22, 2017

Almost, Maine Where: The Cultch What: One cold, clear Friday night in the middle of winter, while the northern lights hover in the sky above, Almost’s residents find themselves falling in and out of love in the strangest ways. Knees are bruised. Hearts are broken. Love is lost, found, and confounded. And life for the people of Almost, Maine will never be the same. Runs until: Saturday April 22, 2017

Vancouver Cherry Blossom Festival

Vancouver Cherry Blossom Festival Where: Various locations What: It’s that time of year when the city turns all shades of pink – the cherry blossoms are in bloom! Celebrate with community picnics, fairs, blossomy bike rides, and group walks. The Blossom Barge will be at Granville Island featuring free performances. Runs until: Sunday April 23, 2017

Angels in America Where: Arts Club Theatre What: A tale of companionship and abandonment that takes place when the personal became political. Set in New York City at the height of the Reagan era, Tony Kushner’s modern masterpiece contrasts the lives of five individuals struggling with identity issues alongside the crippling effects of stereotypes and an incurable diagnosis. Runs until: Sunday April 23, 2017

Capture Photography Festival | In Between Dreaming and Living

Capture Photography Festival Where: Various locations What: High-profile exhibitions as well as emerging talent and community participation are in the lens. There will be events in Vancouver’s leading public and commercial galleries, as well as public installations and a series of community-based photo workshops, tours, artist talks, films, and panel discussions. Runs until: Friday April 28, 2017

Warrior: George Littlechild

Warrior: George Littlechild Where: Kimoto Gallery What: In George Littlechild’s new series ‘Warrior’, he has painted 10 portraits (5 female & 5 male) of 10 individual First Nations people who are fighting the good fight for the planet, the environment and mankind. These individuals are dedicated and devoted to making positive change in their community and in the world, so that future generations will have a better place to inhabit. Runs until: Saturday April 29, 2017

Hastings Park Farmers Market

Hastings Park Farmers Market Where: Hastings Park (near the PNE) What: The Hastings Park Farmers Market features a great selection of local produce; nursery items, fish, meat & dairy; artisan prepared foods, baking and treats; local crafts, and of course, food trucks. Runs until: Sunday April 30, 2017

Mom’s the Word 3: Nest ½ Empty Where: Arts Club Theatre What: From the world-renowned creative team behind the Mom’s the Word series comes a new chapter in their stories of family and fracas. Their kids are grown, their marriages have “evolved,” and their bodies are backfiring. Life doesn’t get any prettier, but it never strays far from ludicrous or poignant as the moms continue to mine their personal history for every embarrassing detail. Runs until: Saturday May 6, 2017

Abbotsford Bloom Tulip Festival Where: 36737 North Parallel Road, Abbotsford BC What: A chance to marvel at 10-acres of rainbow-coloured fields featuring more than 2.5 million tulips in a vivid display of breathtaking beauty. Visitors are invited to enjoy the view, get up close with the blooms, tiptoe through the expansive tulip fields, pick their own spring bouquets in the sprawling u-pick tulip field or purchase pre-picked tulips in the “Bloom-Mobile”, an on-site flower shop. Runs until: Sunday May 7, 2017

Western World

Western World Where: Vancouver Improv Centre (Granville Island) What: Vancouver TheatreSports’™ improvisers will demonstrate their lightning fast wit as they play the “hosts” to the audience “guests” in Western World – an improvised parody inspired by the popular TV series Westworld. Runs until: Saturday May 13, 2017

Susan Point: Spindle Whorl

Susan Point: Spindle Whorl Where: Vancouver Art Gallery What: Since the early 1980s, Susan Point has received wide acclaim for her remarkably accomplished oeuvre that forcefully asserts the vitality of Coast Salish culture, both past and present. She has produced an extensive body of prints and an expansive corpus of sculptural work in a wide variety of materials that includes glass, resin, concrete, steel, wood and paper. Runs until: Sunday May 28, 2017

Pacific Crossings: Hong Kong Artists in Vancouver | Sunset, Carrie Koo

Pacific Crossings: Hong Kong Artists in Vancouver Where: Vancouver Art Gallery What: June 2017 marks the 20-year anniversary of the transfer of Hong Kong sovereignty from the United Kingdom to mainland China. In the lead up to the handover, tens of thousands of Hong Kong residents immigrated to Canada, many choosing to settle in Vancouver, and among them were a significant number of artists. Pacific Crossings presents works from well-known Hong Kong artists created after their relocation to Vancouver throughout the 1960-90s. Runs until: May 28, 2017

Retainers of Anarchy

Retainers of Anarchy Where: Vancouver Art Gallery What: A solo exhibition featuring new work from Howie Tsui that considers wuxia, a traditional form of martial arts literature, as a narrative tool for dissidence and resistance. Runs until: May 28, 2017

Caroline Mesquita The Ballad

Caroline Mesquita The Ballad Where: Centre 221A What: A sculptural practice that intertwines the materiality of altered, oxidized, and painted copper and brass sheets with theatrical playfulness. Runs until: Saturday June 3, 2017

Song of the Open Road

Song of the Open Road Where: Contemporary Art Gallery What: Bringing together artists from Canada, Eritrea, Ireland, Sweden, and the US, the exhibition includes works that combine thematically to interrogate ideas rooted in photographic histories, engaging ideas such as veracity, recollection, remembrance, belonging, staging, and how the image documents and records these or is evidence of differing realities. Runs until: Sunday June 18, 2017

Up Close

Up Close Where: VanDusen Botanical Garden What: All the artists represented in this group exhibition find their inspiration while painting on location at VanDusen Garden. The Vancouver en plein air group, initiated in April 2011, zooms-in to the lush vegetation that provides a new dimension of foreground details. The subjects are varied, and so is the medium. Runs until: Tuesday June 27, 2017

Xi Xanya Dzam – Those Who Are Amazing At Making Things Where: The Bill Reid Gallery What: Xi Xanya Dzam (pronounced hee hun ya zam) is the Kwak’wala word describing incredibly talented and gifted people who create works of art. The exhibition is both a showcase and a critical exploration of ‘achievement’ and ‘excellence’ in traditional and contemporary First Nations art. Runs until: Sunday September 4, 2017

The Lost Fleet Exhibit Where: Vancouver Maritime Museum What: On December 7, 1941 the world was shocked when Japan bombed Pearl Harbour, launching the United States into the war. This action also resulted in the confiscation of nearly 1,200 Japanese-Canadian owned fishing boats by Canadian officials on the British Columbia coast, which were eventually sold off to canneries and other non-Japanese fishermen. The Lost Fleet looks at the world of the Japanese-Canadian fishermen in BC and how deep-seated racism played a major role in the seizure, and sale, of Japanese-Canadian property and the internment of an entire people. Runs until: Winter 2017

Bill Reid Creative Journeys | Image via the Canadian Museum of History

Bill Reid Creative Journeys Where: The Bill Reid Gallery What: Celebrating the many creative journeys of acclaimed master goldsmith and sculptor Bill Reid (1920–1998), this exhibition provides a comprehensive introduction to his life and work. Runs until: Sunday December 10, 2017

Amazonia: The Rights of Nature

Amazonia: The Rights of Nature Where: UBC Museum of Anthropology What: MOA will showcase its Amazonian collections in a significant exploration of socially and environmentally-conscious notions intrinsic to indigenous South American cultures, which have recently become innovations in International Law. These are foundational to the notions of Rights of Nature, and they have been consolidating in the nine countries that share responsibilities over the Amazonian basin. Runs until: January 28, 2018

What are you up to this weekend? Tell me and the rest of Vancouver in the comments below or tweet me directly at @lextacular

Inside Vancouver Blog

0 notes